I’ve been running homelabs for so long and have had some self hosted service or other almost all the time. I swear it has nothing to do with my tendency to hoard old tech in “recycle” disguise. 😀 Anyway, this is me planning a big migration, and I wonder what I’ll see when I read this article in 5 years.

What was wrong with the old setup?

While I could rant on config drifts and standardization all day, the underlying reason is simple for my use case, and as strange as it may sound, it’s mostly repurposing old hardware. My entire homelab setup is repurposed old hardware. Many types of workloads that a home user could need can run on the old daily driver laptop that you bought 10 years ago. If you know your workload, you can increase that number. Maybe not for running LLMs locally, or most modern HPC things, but a self hosted cloud service like Nextcloud shouldn’t want a brand new monster just to hold the family photos from your phone.

So my setup consisted of my old Thinkpad x220 with 16GB of RAM, 128GB M.2 SSD and a 1TB spinning disk, and my old gaming/workstation rig. The Thinkpad, being battery backed by itself and having the better storage/uptime ratio with ZFS, runs those services I want 7/24 online, like my Nextcloud stack, or media streaming things. I’d retired it years ago when the keyboard broke (not as impressive as this one) and turned into a home server. It ran Debian for years, then Arch for another set of years. To be honest, it just worked, but it was messy with completely random ways of running things -I would spin up LXC containers most of the time just because I could do that blindfolded, but used Docker containers if I felt like that night, and even things configured to run on the base system (read: no containers) in the limited time not enough to prepare properly between dropping the kid to the Karate school, and picking her back up. The old PiHole was configured from a parking lot, hopping to the home network from my VPS somewhere in Germany with Wireguard. Guerilla Sys Administration at its best.

The gaming rig? It’s also from 2012 or so. An AMD FX-8320, base clock slightly overclocked, 32GB of RAM, all on a Gigabyte GA-990FXA-UD3, inside a Silverstone Fortress FT-02. The motherboard has 4 PCIe x16 type slots, suitable for up to 4 run-of-the-mill graphics cards (though, of course, not all of them work x16). It was a pretty interesting experiment; my flow was completely virtualized, including my main Linux desktop -in fact, I started with Xen, and moved to KVM later. Three PCIe slots were occupied by three graphics cards, each assigned to a VM by passthrough; one low end graphics card for my Linux VM, a used Quadro for my “professional practice” Windows VM (I worked as an Automotive R&D Engineer back then), and the third, an AMD gaming graphics card, for my gaming VM. I use that box to practice to keep my familiarity with Microsoft ecosystem these days.

Anyway, you’re seeing the pattern? Those computers do work fine for some workloads even today. Naturally, I’m not planning to invest in a full hardware replacement. On the other hand, these machines will eventually become inadequate in terms of specs and resources. I have yet to fill them to the brim but I expect them to be memory-limited, specifically. And specs-limited? Yeah, that’s a thing too. Neither the Thinkpad (with its Sandy Bridge CPU), nor the big boy (AMD Piledriver architecture) can run the current versions of RHEL due to the move to x86-64-v3 microarchitecture level. I’m currently using Almalinux builds that support these CPUs, but I added a third machine to my virtualization fleet for the future; a post-2020 laptop with Intel Tiger Lake architecture. That machine is not really designed for expansion by the end user, so is planned to be run for its processing power and RAM, using network storage.

By now, some of you might have recognized this pattern to be some kind of poor man’s horizontal scaling and shifting towards a cluster. As my workload outgrows my existing machines, I’ll add new boxes, shuffling services from the older ones to the newer one when required. The aging hardware will also become another liability; one day I won’t be able to access one of them.

Why Proxmox? Oh, and how?

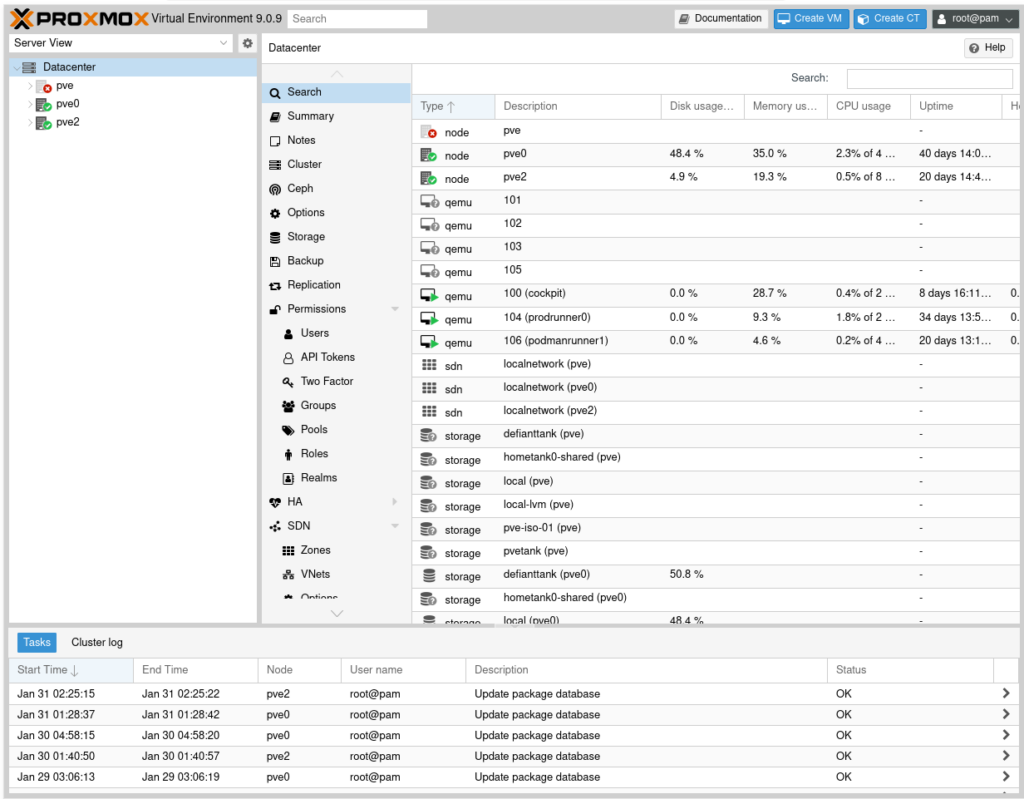

The primary motivation is simple: I want to manage all my virtualization hosts from a single, unified interface. This includes the Web interface as well as CLI, API, and IaC.

The first benefit is the Web Interface. Now I can “see” all my virtualization boxes from the Proxmox management web interface of any host.

The management plan is to use Terraform to spin up resources (full VMs or LXCs); I have yet to try the Proxmox provider but initial research shows others are happy with it. Then I’ll be using Ansible to do configuration management inside the resources. I think this fits my flow, even though I might be biased due to habits and prior experience. I’m open to suggestions.

And the third benefit is to be able to shuffle workloads between machines. As mentioned, if my old x220 starts acting up, I’ll want to shift the loads on it to others before it gives up the magic smoke. Or maybe I’ll find that a certain service outgrows the machine it is running on, which is another reason to migrate it to another host.

High Availability is not something I’m planning for yet. That will require extra hardware, especially a bigger UPS. Maybe in time, as it is waiting for me as a feature in Proxmox.

I realize none of these require Proxmox in a strict sense except unified web interface -even that can be replicated. But my experimenter side also pressed, “I know you want to learn Proxmox, and more Terraform, and more Ansible… You know you do…”. So here I am. 🙂

It took me maybe half an hour to install Proxmox on two nodes and join them to form a cluster. The latest addition to my fleet took even less to include in the cluster. Now, clusters with even number of nodes are better off with some more planning, and a 2-node cluster can be a bit problematic. Proxmox uses “Quorum” to decide the way it works. Basically, each node in a cluster “votes”, stating they are operational, and the cluster works as long as the number of votes is higher than a threshold… which is (n/2)+1 where n is the total number of nodes. A two-node cluster falls back to running in a degraded state if one of the nodes goes offline as it requires (2/2)+1=2 nodes to run. You won’t be able to launch new VMs, and none if the remaining node also restarts. There are a number of workarounds to this:

- Add a third device, maybe a Raspberry Pi, not to run workloads even. Perhaps monitoring other nodes.

- Use a QDevice. This is also not intended to be a real workload-running Proxmox. In my case, I could have used my network storage box, which I do not wish to have in a cluster, to run the necessary daemon.

- Configure one of the nodes to provide more than 1 vote

- Configure nodes to require a lower number of votes to continue functioning

The recommended approach to this is to use a third device, a dedicated device if possible, or use another machine to run the daemon. Proxmox is Debian based, and if you have another Debian box, you should be clear. The last “solution” is especially problematic, don’t do that except troubleshooting in a controlled environment, or you might cause a split-brain condition. And for <insert_deity_here>s sake, don’t use a VM to vote, unless you know what you are doing in very specific situations. Tip: I don’t see any of those specific situations in a prod environment. 🙂

Before the third node came, I used my network storage box to provide a vote as a qdevice. When I increased my number of nodes to 3, two of which on battery backup power, I no longer needed that.

Anyway, let’s reiterate my nodes:

- Node 1: The Thinkpad x220. 16GB of RAM, 128GB SSD, 1TB hard drive, on a dock, with good battery

- Node 2: An old AMD FX-8320, overclocked to 4GHz base clock, 32GB of RAM, not battery backed

- Node 3: A ~5 year old laptop with Core i7 CPU, 16GB of RAM, 512GB storage

Every machine will have a job to do. My initial plan is:

- Node 1

- This one will run my controller VM, which will be responsible for storing my Terraform files and Ansible playbooks, as well as other config/control related business applicable to all other workloads. This one also control my VPS elsewhere. In addition to being the single source of truth, I’m expecting this to help me consolidate my environments. I use multiple computers daily, and would really like to not bother shuffling them just because I want to do stuff on my homelab. This way, I’ll simply SSH into the controller node, no matter which client I have on my lap.

- Nextcloud, Redis, and Postgres. Now, I might migrate Postgres to a bigger node, depending on future workload as it will function as my primary DB for all other services as well, but this box worked fine for my light load Nextcloud stack so far. I am not expecting any big increases on load for these. Also, this has the bigger storage among my battery backed rigs, making it a better fit for Nextcloud

- Vaultwarden, I guess. Never tried before, but it has been in my mind for some time

- Some in-family communication services -alternative to using Whatsapp and the like for family

- Calibre – copying ebooks to multiple devices is… not preferred. 🙂

- Bittorrent client, likely Transmission

- Media streaming

- Node 2

- A Windows machine with GPU passthrough, in case I want to play a game

- Other than that, it’s mostly my experimental machine. That’s why it is not battery backed. Most loads would be things like a Windows Server to help my Win ecosystem learning adventures

- Node 3

- paperless-ngx and its dependencies.

- Lubeguard

- Testing things that require more recent CPUs

This was a summary so far. I think the next article will be about creating a VM template. I’m planning to use AlmaLinux as my intention is to converge my fleet on Red Hat ecosystem, migrating from Docker to Podman in the process. Let’s see what comes next.