I’ve mentioned ZFS before, but as I’ve used it more, I realized it deserves its own series. In this series, I will avoid academic fluff as much as possible and focus on practical, usage-oriented information. My goal is simple: to enable you to start using ZFS in your own systems just by reading these posts.

I will link new articles here as they are published. If you want to follow my ZFS series, check this page occasionally. Once finished, this will serve as a central hub for everything you need.

Tell me about ZFS

Simply put: For our purposes in this series, ZFS is a combined file system and logical volume manager that allows you to create massive, highly secure storage pools using consumer-grade disks (the kind you buy at a local tech shop) without needing expensive “enterprise” drives. For simplicity’s sake, I’ll just call it a file system.

;

The system above can be just moved to the server room, with quite good data reliability confidence. Storage cost around $40 per TB.

Let’s start by listing some of its core features:

Data Integrity: Reliability far beyond what traditional RAID can offer.

Self-Healing: It can detect and repair corrupted data automatically.

Massive Scalability: We’re talking 340 undecillion Terabytes (if I missed a few zeros, let’s not make a big deal out of it! :D).

Integrated Volume Management:

Sub-partition management via Datasets and ZVOLs.

Per-partition settings for snapshots, compression, deduplication, etc.

Instant, near-infinite snapshots with zero performance hit.

Native Compression: Writes all data in compressed form.

Block-Level Deduplication: Saves space by storing identical blocks only once, even across different files.

Intelligent Caching: Caches not just “Most Recently Used” (MRU) data, but also “Most Frequently Used” (MFU) data.

External Caching: Ability to use dedicated disks (like fast SSDs) for cache.

Ease of Use: Simplified command-line management.

Data Integrity

First off, ignore anyone saying, “Well, we use RAID 1500, so we don’t lose data.” 🙂 You cannot reach ZFS levels of data security with cheap disks on any standard RAID mode. Actually, RAID has more to do with data availability, but not necessarily with data longevity.

The key phrase for enterprise storage is protection against data loss. Every hard drive eventually encounters an “Unrecoverable Read Error” (URE). Every hard drive eventually has a flipped bit. The high price tag (up to 2x-4x the cost of a regular hard drive) your IT department pays for enterprise disks is essentially paying for a drive that is less likely to hit those UREs, flipped bits, bit rots -anything that changes those bits unintentionally and silently.

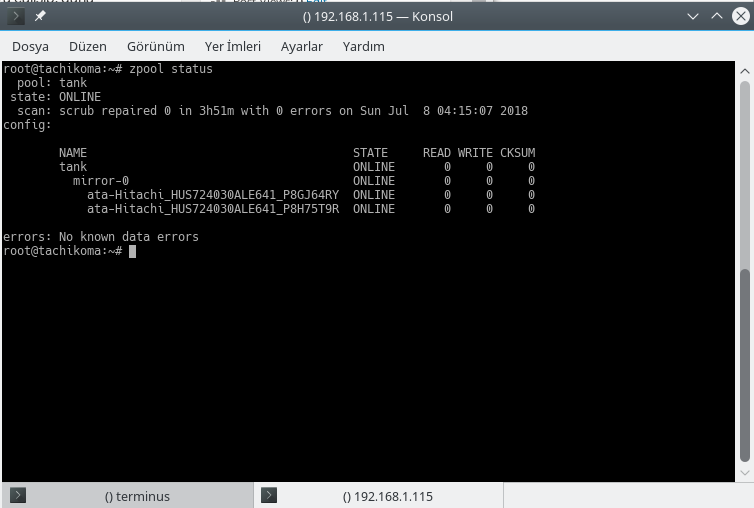

ZFS solves this by keeping a checksum for every block of data it writes. To verify if data is corrupt, ZFS simply recalculates the checksum and compares it to the stored one. In practice, we use this with mirrored or parity-based disk groups.

These two disks are copies of each other. Think of it like RAID 1.

ZFS periodically scans (scrubs) these disks, recalculates the checksums, and compares them. If an error is detected in one, ZFS simply pulls the correct data from the other disk and repairs the corrupt part. This is the “self-healing” magic.

On my home server, I run this check once a month (the last Friday night). In enterprise environments, a weekly scrub during off-peak hours is standard practice.

The Resilvering Advantage

Beyond “silent errors,” there’s the risk of total disk failure. In traditional RAID, when you replace a failed 3TB drive, the controller must read the entire 3TB from the healthy drives to sync the new one—even if you only had 1TB of actual data on it. This can take days. During this “rebuild” time, your system is vulnerable, under heavy load, and the risk of a second drive failing increases significantly.

ZFS, however, is “metadata-aware.” It knows exactly where the data is. It only copies the used blocks. If your 3TB disk is only 30% full, the “resilvering” (rebuild) process will be much faster and safer.

Storage Management

ZFS isn’t just a file system; it’s a volume manager. You create a “Pool” (often named tank in documentation). Under Linux, this pool is mounted under the root directory by its name. From there, you can “partition” it as you like.

I primarily use Datasets. Think of them like directories, but with “superpowers.” You can toggle features like compression or deduplication for each dataset individually. For example, you can set one dataset to take snapshots every 15 minutes, while another takes them once a day.

There are also ZVOLs, which act like block devices. You can format them with other file systems (like NTFS or XFS). This is useful for applications that aren’t ZFS-native—for instance, if you’re setting up an MS SQL Server, you’d create a ZVOL and format it with a compatible file system.

RAID Levels: VDEVs and RAIDZ

In ZFS, a pool is made of VDEVs (Virtual Devices). If you want, you can just use 4 disks as 4 VDEVs -ZFS distributes data on these disks, creating a RAID0-type configuration.

For self-healing and resiliency, we would usually prefer a RAID1-style configuration, or RAIDZ. The first is like a mirrored RAID array; every VDEV consists of (at least) two disks. For the 4-disk setup I just mentioned, that would be 2 VDEVs, each consisting of 2 disks. Capacity drops to half the total capacity of your four disks, but data loss risks are greatly reduced.

RAIDZ (RAID 5/6 Style) is a parity-based setup. It is normally faster than a traditional RAID5 array and avoids the “write hole” error. We use numbers to denote “levels”, like RAIDZ1 (tolerates 1 disk failure), RAIDZ2 (tolerates 2 failing disks), etc. It is also more space-efficient than mirroring.

Caching: ARC, L2ARC, and SLOG

I mentioned that ZFS caching takes data (blocks) use frequency as well as how recently it was used. By cache, we mean “faster storage, but lower capacity”. Obviously, they get filled fast. 🙂 Traditional caches use an LRU (Least Recently Used) algorithm—when the cache is full, they dump the oldest data.

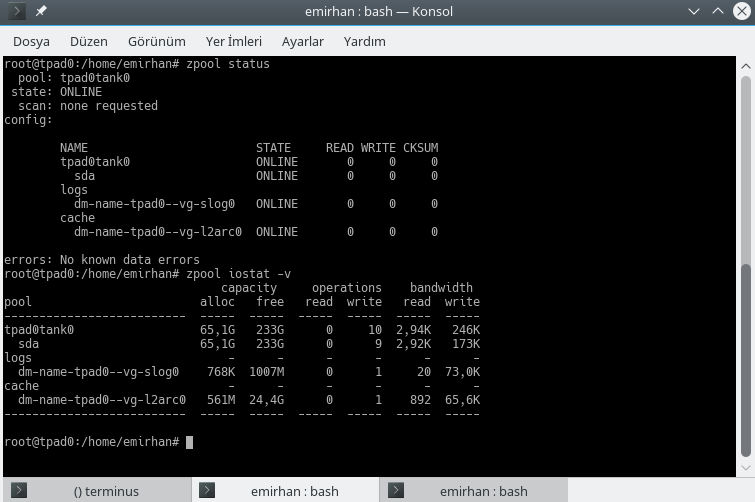

ZFS uses ARC (Adaptive Replacement Cache), which tracks both recency and frequency. If you have a 5GB file you use every day, ZFS won’t dump it from the cache just because you temporarily moved some large, unrelated files. Data is normally cached in RAM. This fact accounts for high RAM recommendations for ZFS -and I’m not talking about just the data, but metadata. The read cache is called ARC; Adaptive Replacement Cache (or Adjustable rather than Adaptive, in some sources). RAM is a severely space-limited medium (read: Expensive!), but you can also show an SSD to ZFS and just say “Hey, you can use this one as a cache”. This sort of cache is called a Level 2 ARC (L2ARC). You can add or remove L2ARC as you like.

The way this works is, assume you have 24TB of “rusty” storage (i.e. spinning disks, magnetic storage, traditional hard disks), and 32GB of RAM. You also have a number of virtual machines on this host. You can only store so much of data for all these data users in RAM, as it is needed for other tasks, and is small to begin with. You can assign a 128GB SSD as L2ARC, for instance. ZFS will tend to keep a copy the most frequently used data, in this case, operating system data for the VMs, in the SSD. This way, you can plan your storage more efficiently.

We discussed the data-reading part until now. There’s also the write side of it. ZFS write caching “combines” data as best as it can, and writes in “transaction groups”. At the time of writing this, this write/flush operation period is generally around 5 to 10 seconds. It works async, the application that requests the writing operation is notified like “I got the data, you go ahead and mind your own business”, and helps with spinning disks’ weak side -they are happiest with sequential RW, meaning they are quicker to write a single transaction with N mebibytes than N transactions with 1 mebibyte. ZFS can also optimize the actual placing of data this way.

This brings us to the third caching mechanism, the ZFS Intent Log (ZIL). You would ideally want to write the data you “collected” in RAM to somewhere permanent sooner than later, as a power interruption can mean you lose data. ZIL and its friend on preferably an SSD (fast storage!); the Separate Log (SLOG). ZIL is always there, if you don’t have an SSD to help, the actual disks are used for this. SLOG can help with lowering data loss risks.

How much of a risk? I think any data loss risk is bad, but worst case, you usually lose the last 5-10 seconds worth of data, if any. But remember that those 5-10 seconds worth of data would not necessarily be your game saves, they could be a part of a much larger set, and can render a lot of data invalid if they’re lost.

Compression and Deduplication

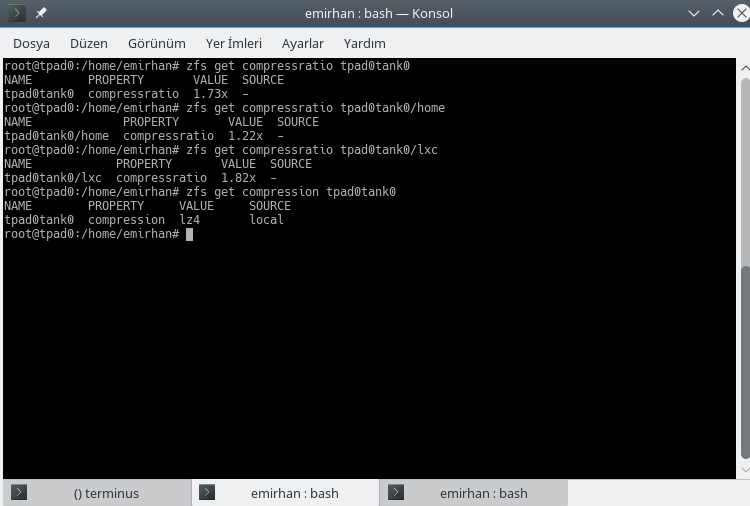

Compression can be activated and deactivated on a dataset basis, and it is even possible to use different compression algorithms on separate datasets. The default is lz4 at the time of writing, and that’s what I use.

Compression is almost transparent in terms of system load on my current laptop, a Lenovo Thinkpad X220. To interpret my stats, I have a large amount of already compressed data, which is why the home directory shows a lower compression ratio. But the overall ratio is around 1.7, which is close to what my workload ends up.

And the famous (infamous?) deduplication. It’s tempting, to say the least, in theory. My go-to example when I’m explaining this topic is “director’s cut” versions of movies. Sometimes, there are multiple endings, or alternate/extended scenes in DVDs (or nowadays, BluRay discs). The bulk of the scenes are the same with the theatrical edition, except these additions. Assume you have 3 versions of the same film; one of them is the theatrical edition, occupying 9GB of space. The others are the “editor’s cut” with alternate endings and “extended edition” with extra/longer scenes, occupying 10GB and 12GB, respectively. Total storage requirement is 31GB. But notice that the 9GB part is the same for all three, in other words, duplicated. You can store this 9GB section once, “deduplicating” the three duplicates, and all three versions would occupy only 13GB of disk space.

I know this looks apetizing, but there’s a catch: Deduplication requires lots of RAM to work well. ZFS needs to keep track of each deduplicated block, and wants to keep all these in cache, increasing memory pressure. I have only used deduplication feature for testing purposes, and it’s disabled in my normal flow. My workloads make spending my money for storage rather than RAM more logical.

Backups: Send and Receive

ZFS makes backups incredibly simple with two built-in commands: zfs send and zfs recv. You take a Snapshot (an instant, read-only “photo” of your data that takes up zero extra space initially), and you can “send” that snapshot to almost anywhere.

Under the hood, zfs send command creates a pretty ordinary data stream. You can redirect this stream to a file if you like. But the interesting part is redirecting this to another machine. As this is an ordinary stream, compression and encryption can also be provided by standard Linux, all in a one-liner.