There is a common misconception I hear often: the belief that RAID is a sort of “data amulet” that protects you from all misfortune. While a simple storage box for your home movies might be fine with basic RAID, if you are storing critical data, this can lead to a dangerous false sense of security. I’ve been waiting for the right moment to share one of my favorite quotes in this blog: In the end, it’s all just a matter of probability. 🙂 Data in your information systems can be corrupted at various stages for various reasons. Even though hardware and software try to correct these through different methods, there is always a residual risk. Even cosmic rays falling to Earth from space can corrupt your bits. And I’m not talking about a hard drive physically failing and going offline—I’m talking about silent data corruption, or the types of data corruption you are more likely to encounter when you’re at your most defensless hours: rebuilding RAID arrays.

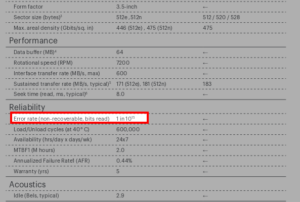

Hard drive manufacturers provide statistical data regarding this degradation. As I mentioned in my post about ZFS, one of these metrics is the Unrecoverable Read Error (URE) rate. Below is a screenshot from a datasheet of a drive commonly found on the market.

For this model, it specifies 1015. As I explained before, this essentially means: “Statistically, I will make a one-bit error for every 10^15 bits I read.” In simpler terms, that is one bit error every 125 Terabytes (1).

You shouldn’t think of this as “I’ll read exactly 125 TB and then an error happens.” Rather, it means a one-bit error is likely to occur somewhere within those 125 TB. It could be the very first bit, the last one, or anywhere in between. However, as the amount of data read approaches 125 TB, the probability of encountering an error rises toward 1 (100%).

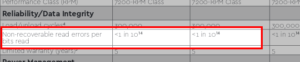

Let’s look at two more examples. The next one shows 1014 bits—an error every 12.5 TB. This is typical for a standard consumer drive you’d buy at a local tech shop for a home PC.

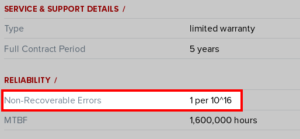

The final example is from the enterprise storage class: an error every 1016 bits. Roughly 1.25 Petabytes (PB).

The reason you might only be hearing about this now is simple: the volume of data we store is growing exponentially. These statistical rates have been roughly the same for years, but back when a 250GB drive was “huge,” the chance of hitting the limit was low. Today, home users start with 2TB drives, and enterprise storage operates on a different scale entirely. Consequently, the probability of performing enough data transfers to trigger these errors has skyrocketed.

The Relationship Between Error Rates and RAID 1

In a RAID 1 setup, you keep two or more disks as identical copies. Dual-disk mirrors are the most common.

Imagine you have a mirror group consisting of two 10TB hard drives. One fails, and you replace it with a new one. Your RAID array must now read the entire healthy disk from start to finish to copy the data to the new drive. As the amount of data you read has increased, your likelihood of hitting that URE has also increased.

If you are using consumer-grade disks (1014), the statistical likelihood of this happening during a rebuild is uncomfortably high. If the new disk fails (it happens), you are critically close to a URE as you had already read a lot of data during your previous rebuild.

And if that “healthy” disk reads a single bit wrong…

You’ve just “flipped” a bit and wrote it in the new disk. This is worse than a simple failure: you now have inconsistent data, you aren’t aware of it, you don’t know which version is correct, and by the time you realize it, it might be too late.

Disk Load During RAID Reconstruction

Disks wear out with use, and the probability of failure increases over time. This is why you see so many specialized product lines today. The wear on a home drive used 3 hours a day by one person is vastly different from an enterprise drive responding to dozens of simultaneous requests 24/7.

When a disk in your RAID array fails and you replace it, the system uses the data on the remaining drives to rebuild the new one. During this process, the system is also trying to handle normal user requests. The load on the “surviving” disks increases significantly.

This is precisely when the chance of a second disk failing is highest—especially if all your disks were manufactured in the same batch. If the second disk in a 2-disk RAID 1 array fails under this stress, your data is gone.

The RAID 5 “Write Hole”

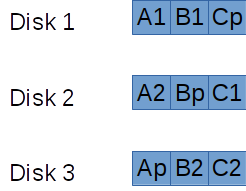

With storage costs being so low now, I rarely prefer it, but there is also RAID 5. This requires at least 3 disks. In every write operation, the data itself and a small piece of parity (control) data are written across different disks. The advantage over RAID 1 is capacity efficiency.

In the diagram, ‘p’ represents parity. If you look at block A, A1 and A2 are the data, while Ap is the parity. If any one disk fails, you can reconstruct the missing data using the other two.

But what if the power cuts out exactly while the parity data for one of these groups is being written? When you reboot, the system will continue to function, and you likely won’t know there’s a problem until a disk actually fails. It’s a ticking time bomb. 🙂

In practice, Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPS), battery-backed controller cards, and other strategies can significantly reduce this risk. Still, RAID 5 should not be trusted blindly. Note that the “write hole” issue affects almost all RAID levels to some degree.

Notes

- I am referring to ‘Tera’ in the SI unit system (powers of 1000, not 1024). The version based on 1024 is technically called a Tebibyte (TiB). Similarly, Petabyte is SI; the 1024 version is a Pebibyte (PiB).