More efficient resource management, “lightweight” virtual machines that spin up in seconds, and simplified administration. Welcome to the world of container-based virtualization. I promise not to get too deep into the technical weeds this time. 🙂

In my lab, I use LXC for container virtualization. I started with it because of its simplicity (I’ve been managing full Linux machines since 2000) and have stuck with it ever since. Whether it’s Jails on BSD, Solaris Containers, or the newer LXD, the core philosophy remains the same. In this post, we’re looking at LXC.

Actually, this isn’t a “new” idea; it has been around for years. However, if you’ve spent most of your career in a Windows-centric IT environment, you might not have encountered it often. Simply put, imagine the operating system kernel can assign a “tag” or “identity” to the processes (1) it runs. With this identity, the kernel can treat groups of processes as if they are coming from separate virtual machines.

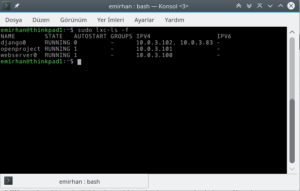

Essentially, you declare a folder on your disk as sort of a “virtual machine,” populate it with the necessary files (the root filesystem), add a simple configuration file to tell the system how to handle it, and—ta-da! Below, you can see the containers running on the machine I’m using to write this article.

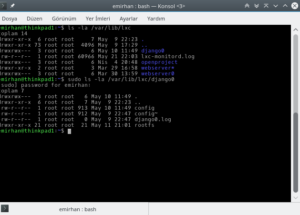

And here are the “virtual machine folders” I mentioned:

You can see three containers here (I made a typo in one, but I was clearly in a hurry!): django0, webserver0, and openproject. In the next command, I looked inside the django0 container. Two items are key:

- rootfs directory: This folder holds all the system files for the virtual machine.

- config file: This holds the settings, such as the MAC address for the virtual ethernet card and IP configurations.

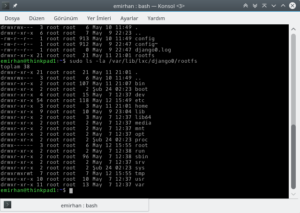

I know you might expect more complexity, but it really is this simple. If you don’t believe me, look at the contents of the rootfs directory:

These are the same files you would see on any standard Linux installation.

So, what are the actual benefits?

1. Near-Instant Provisioning

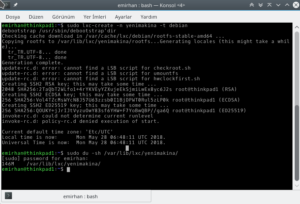

A virtual machine is essentially just a group of files downloaded into a folder. Because these templates are cached, creating a second instance of a specific OS type is incredibly fast. I recorded a quick demo for you on my 2011 ThinkPad X220, showing how I spin up a new Debian container using a template:

2. Minimal Resource Footprint

Did I mention you aren’t installing an entire separate kernel? Look at the disk size of the container I just created:

3. Seamless Resource Management

When setting up a full-stack VM (like KVM), you have to explicitly allocate and optimize disk, memory, and CPU. In LXC, your “virtual machine” is just another process to the host kernel. It manages resources dynamically.

This allows for much higher density. You don’t have to worry as much about “How many GB did I give to whom?” In a traditional VM, if you split 16GB of RAM between three VMs and give them 8GB each (yes, you can overprovision!), you hit performance walls the moment one needs more. With LXC, the Linux kernel handles the memory allocation on the fly, avoiding those hard limits.

4. Performance and Efficiency

Before you think this is “magic,” keep in mind that even a well-tuned KVM setup is only about 2-3% slower than bare metal. LXC, however, runs at the native speed of the host OS.

Because containers are just processes to the kernel, it allows for clever technical tricks. If three LXC containers are running the same OS, they likely hold similar data in memory. Instead of keeping three separate copies, the host kernel can often serve that data from the same memory space (2).

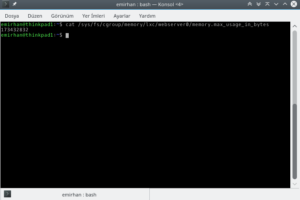

Below, you can see the memory usage of my webserver0 container, which hosts my personal Wiki (MediaWiki). It’s only using about 160MB.

While a single VM might only be 2-3% slower than a container, the aggregate system load tells a different story. A hypervisor (like KVM) adds its own overhead for managing the VMs and translating instructions. With container-based virtualization, you can comfortably run significantly more “machines” on the same hardware.

The Downsides and My Personal Workflow

Any expert will tell you: if you aren’t in a controlled environment, you need to learn about unprivileged containers, SELinux, and AppArmor. Full virtualization (KVM) has the advantage of better memory isolation—breaking out of a guest VM to the host is much harder than in a container.

Also, a note for my Windows friends: You cannot run a Windows container on a Linux host using LXC. Containers share the host’s kernel, and they are “kernel-less” entities themselves. 🙂

My hybrid setup:

- Isolation: I use LXC for isolated services that don’t need to “talk” to each other much.

- Long-term Services: Web servers and databases are all in LXC. I take regular ZFS snapshots of these images, making it easy to migrate them if my main host fails.

- Testing: I use “disposable” LXC containers for testing new Linux apps. It’s cleaner than cluttering my host.

- Desktop & Windows: I still use KVM for desktop virtualization. Passing through a GPU or specific USB ports is much more straightforward. And, of course, for Windows, KVM is the only way.

Notes

- Technically they are “process groups,” but I simplified it as “programs” for this context.

- KVM uses similar technologies (like KSM), but it’s much more native and “automatic” in LXC.

- Sharp eyes might notice I’m using “privileged” containers in the screenshots. Honestly, on my personal machine, I’m just too lazy to configure the mappings! 🙂 Joke aside, if you’re reading this for an enterprise application, for

‘s sake, don’t do it. You want unprivileged. Trust me.