ZFS carries advanced caching features. In this article, I will assign a cache to your ZFS pool and discuss both its impact and how it operates.

ZFS Caching and Strategies

We can roughly define caching as storing data we will need sooner in a fast location. Since the general trend in all types of storage is that price increases as speed increases, caches are typically small in size. Even the caches in processors (labeled as “cache”) are very small due to space constraints.

You don’t necessarily need to use something special as a cache. Anything faster than the location where you store the primary data can be a cache. If your data is on a tape cassette, a normal hard drive can be your cache. You can take data from such magnetic disks and cache it onto an SSD. In practice, the fastest cache is RAM itself. All operating systems want to use RAM as a cache as much as possible.

Now, we said the cache area is limited—if it weren’t limited, we would store all the data in the thing we use as a cache anyway. Therefore, we need strategies to select the data we will keep in this cache because we don’t want unused data to occupy space. A common strategy is to kick out the oldest data in the cache; the “Least Recently Used” (LRU) piece of information. This strategy assumes that information recently read from the disk has a high probability of being read again.

ZFS, in addition to this, also uses a strategy of keeping the most frequently used information. If a certain group of data in your cache is used more frequently than others, it tries to keep this data in the cache.

Let’s detail the difference between the two. Suppose you have a cache of 100 units. You read every data request from your hard disks and write it here. If the same data is requested in the future, you don’t need to go to the hard disk and read it; you fulfill it quickly from here. Until it’s full. When the cache is full, you need to eject as much as you’re going to write from the cache to write something new. Which one will we eject?

The LRU strategy tracks the order in which it wrote the data pieces to the cache and ejects whichever is the oldest from the cache. You can see the disadvantage of this in a system where a certain type of data is normally used a lot, but at a moment when this frequent use is absent, another group of data is requested once. The newly requested data might be requested once and never used again, but you empty the cache and put it in. You will wait for all the data you normally use a lot to be read once more to get it back into the cache.

ZFS tracks how frequently the pieces in the cache are used as well as when they were used. Think of it as a certain portion of the 100-unit memory above being kept for frequently used data. New data would normally fill the 100-unit area, but ZFS allocates it perhaps a 75-unit area and refuses to eject the rest from the cache (because it is frequently used).

The name given to ZFS’s cache is Adaptive Replacement Cache (ARC). In some sources, it is also called Adjustable Replacement Cache. ARC is normally in RAM—this is where the recommendations for having plenty of memory for ZFS come from.

Second-Level ZFS Cache: L2ARC

As some of you might have guessed, L2ARC simply stands for “Level 2 ARC,” the second-level cache. L2ARC can be a disk partition. We generally use SSDs, or in some cases, fast USB disks if we have plenty of them. An L2ARC cache is added to a ZFS pool with the following command:

zpool add tank cache /dev/sdf

This basic command has a drawback: node names like sdf and sdb are determined according to the disk order given by the motherboard. Some motherboards might not assign these node names in the same way at every boot. Or someone might mix up the disks and their order connected to the SAS/SATA ports during maintenance. In such a situation, the disk you know as sdf today might appear as sdg tomorrow. Since your ZFS pool recognizes that disk as sdf, whatever disk the friend who mixed up the SATA cables plugged into the slot corresponding to sdf will be mistaken for the cache.

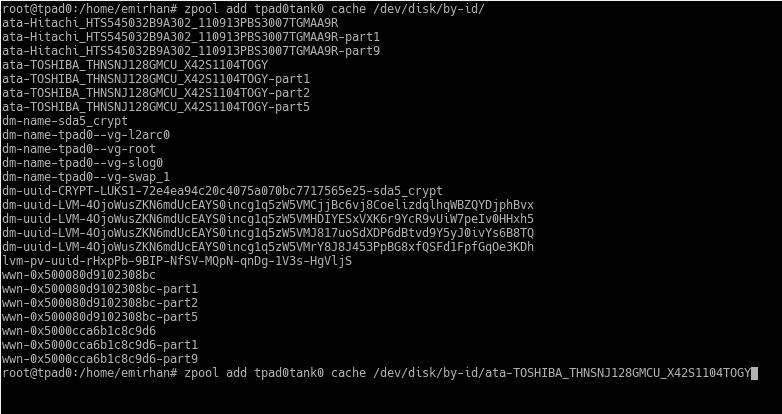

Therefore, it is correct to do this with the names under /dev/disk/by-id. For my system, it looks like this:

The thing starting with ata-TOSHIBA… is the SSD in my system. You see sections like part1, part2 at the end because I also use it as a system disk and have partitioned it. Yes, in ZFS you don’t necessarily have to use the entire disk as a cache; you can use a block device, which can also be a partition of a disk.

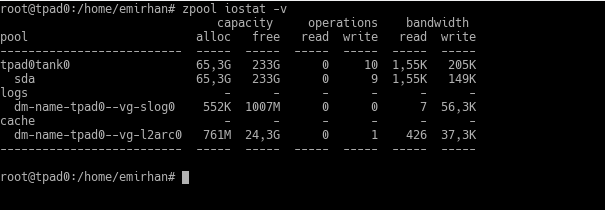

After adding L2ARC, you wait for it to fill up to see the benefits. This depends entirely on how much the system is used. If there are a lot of random reads, it will fill up quickly, or an L2ARC you add on a Friday evening might only start to fill up meaningfully on Monday after the employees come to work. Again, from my Thinkpad:

Hmm, 761MB cache usage? Because I restarted the computer in the last few days. When the system restarts, L2ARC is invalidated and starts being filled again. You also see that my total L2ARC size is 25GB, where I should convey a note: it’s not mandatory for the entire disk you assign as L2ARC to be filled. The data in L2ARC creates records within the ARC in RAM. In other words, you can use L2ARC in an amount proportional to the space you can allocate for these records in your RAM. This requires a calculation involving block size and the size of the records, just as in deduplication.

ZFS ARC also avoids caching sequential data transfers. Sequential data transfer is an area where hard disks are good enough; they struggle with random access. Thus, the SSD you added as a cache is used primarily for its own strength, random access, and is not pointlessly occupied with data already read quickly from the hard disk.

ZFS Intent Log and SLOG: How ZFS writes?

To explain the ZFS Intent Log (ZIL), it’s necessary to mention two methods programs use to write to the hard disk: Synchronous and Asynchronous. It’s not actually that difficult.

If the program continues its operation without waiting for the information that the data it sent to be saved to the hard disk has actually been saved, it is providing asynchronous access.

If it does not continue to work and waits until the information that the data it sent to be saved to the hard disk has actually been saved arrives, it is providing synchronous access.

Data that programs providing asynchronous access want to save can be kept in memory by the operating system and saved to the disk at a convenient time. The program doesn’t care. But a program providing synchronous access waits for the information “I saved your data in a safe place, continue” from the system, no matter how many seconds it takes. Databases or protocols like NFS generally prefer synchronous access; they don’t want the data they will write to stay in RAM and disappear in a situation like a power outage.

ZIL can be thought of as an area, a kind of notebook, used to make records quickly without dealing with the data structures on the hard disk. ZFS saves the data that a program requesting synchronous access will save to the ZIL as well as keeping it in RAM, and sends a “data written, you continue” signal to the program. Thus, the “saved to stable storage” condition of the synchronous write request is fulfilled.

These write requests reach their final locations at specific time intervals (every 5 seconds for ZFSonLinux). ZFS organizes the accumulated write requests and turns them into transaction groups. In this way, it writes to the hard disk in an orderly fashion.

So, the ZIL exists only for those 5 seconds (or however many seconds are specified in your system). In the event of a power outage or another failure that causes the system to stop, those last few seconds of data can go “poof” along with other information in RAM. At the next boot of the system, ZFS reads the ZIL and “replays” the data to be written to the disk. Therefore, as long as the system works normally, the ZIL is never read; it is constantly written to.

ZFS allows taking this ZIL record to a separate disk. The area on this separate disk is called SLOG, i.e., “Separate LOG.” Thus, the confirmation for synchronous write requests will be sent in a shorter time, which means a performance increase. Essentially, in a system under load, even taking ZIL records to a separate but mechanical disk can provide benefits. However, in this era, we use fast SSDs, of course.

You add the SLOG to your ZFS pool like this:

zpool add tank log /dev/disk/by-id/disk-identity

With a real example:

zpool add tank log /dev/disk/by-id/ata-TOSHIBA_THNSNJ128GMCU_X42S1104TOGY

Notice that, as in L2ARC, we added this with the disk identity for the same reason (be careful, the command I call a real example is a single line).

You see it in the logs section in my actual screenshot as well.

You determine the size of the SLOG according to the total write speed of your background VDEVs. If you are continuing with the standard installation, there will likely be a transfer to the disks every 5 seconds. This means you should create enough SLOG space for what your disks can write in those 5 seconds. There is a single disk in this system (it’s a laptop, right? :)), and when I tested this disk, I obtained transfer speeds like 70-80MB/s. So, a SLOG of about 400-500MB was sufficient. If there were 2 of these disks and I had made two VDEVs, my total transfer speed would have been around 150MB/s, and I would have needed to leave an area of about 750-800MB for 5 seconds of data storage. Still, it’s beneficial for you to keep this area a bit larger.

Due to the constant writing characteristic of the ZIL, one must be careful with this SSD. First, the write speed must be high. Also, because it will see constant writing, there is a possibility of it dying earlier than normal. Of course, to minimize the chances of data loss, it could also be reinforced with a battery/supercapacitor so that after power is cut, data doesn’t remain in the SSD’s own cache but is written to permanent storage. My recommendation, if budget allows, is an SLC SSD with battery reinforcement.

If there is no budget, a normal, consumer-grade SSD with extra free space left can also be used—accepting early replacement. The reason you leave extra free space is that SSDs have a certain write lifespan. Consumer-grade SSDs are produced with MLC technology, and their lifespan is even more limited compared to SLCs. If you are using MLC, leave your SLOG several times larger than what you calculated; in fact, leave about 10%-20% unpartitioned space on the SSD. The SSD will start using these areas you left free instead of areas that wear out as you write.